In the summer of 1970 John Baldessari drove all 123 paintings that were in his studio, made by the artist from May 1953 to March 1966, to a local mortuary. He proceeded to cremate them. The ash produced by this act was baked into cookies that would later be placed in a vessel taking the form of a leather bound book. In this one action Baldessari shed his practice from the orthodoxies of medium specificity, while at the same time creating the opportunity to conceptualise questions anew about art and his practice within the discipline. The creative impulse at times demands acts of erasure. Beyond action, style or statement, experimentation is the only means we have to question and challenge the habitual. What is of consequence in this pursuit is to challenge everything and enable our understanding of the world. A year after his action Baldessari declared, “I will not make any more boring art”, which led the artist to embark on a life’s foray as a pioneer of what would become known as conceptual art. Experimental practice demands more.

Experimentation – this fluid word within architecture haunts the discipline. To experiment has always stood for something that attempts to go beyond in order to expand the finite orthodoxies of what is taught and the assumptions made in this world. It is an action that affords understanding. Experimentation in method and practice is enabled by curiosity, the desire to create and evolve. Even when the experiment fails it is during this struggle an offering emerges. At its heart experimentation is an attempt to ask more informed questions of the world and our participation in it. This act allows to move beyond building, style, economy, history or discourse. Architecture with all of its paradoxes remains a space for interrogation through this action in time. It challenges us to see history as something plural rather than linear and constructed. Experimentation provides agency.

Architecture is space. While this statement makes a claim, which we may agree on, it still fails to say much. Space like time is a construction. Concepts that have no finite form or understanding though govern much of what we spend our time attempting to relate to. Time is our medium. We live and practice in time and yet time also is not finite. The acclaimed physicist Carlo Rovelli speaks of time as something elastic and is understood as moments in time. Time in quantum physics is something that is unique and situated, rather than assumed and generalised. In his book The Order of Time, Rovelli states that:

We see the world and we describe it: we give it an order. We know little of the actual relation between what we see of the world and the world itself. We know that we are myopic. We barely see just a tiny window of the vast electromagnetic spectrum emitted by things. We do not see the atomic structure of matter, nor the curvature of space. We see a coherent world that we extrapolate from our interaction with the universe, organised in simplistic terms that our devastatingly stupid brain is capable of handling.[1]

A conceptual framework today necessitates an acknowledgment that observers are not outside of the system that they observe. This questions the foundational orthodoxies of observational methods and the finite results that are ascribed to them.

“Heinz Von Foerster expressed this distinction between observed systems and observing systems” as the primary evolution of systems thinking through second order cybernetics or the cybernetics of cybernetics. At a presentation delivered at the University of Illinois, Urbana entitled “Cybernetics of Cybernetics” Foerster reminded the audience of biologist and theoretician Humberto Maturana’s famed proposition, “Anything said is said by an observer”, which he followed up with a call to expand this by adding “Anything said is said to an observer”.[2]

Our observation of the world is ours. This is a radical constructivist approach to philosophy that in summary can be understood as follows: everyone’s observation and understanding of the world is their own and inaccessible to others (be that man or machine). If we expand on this statement the obvious appears: that even in our most objective pursuits in science or math, by necessity we must acknowledge the bias within a system bias in its capacity to observe and understand. These biases are as much embedded in human as they are in non-human observations and learning. In practice one can begin to understand this by looking at recent habit-forming tendencies found in how artificial intelligence operates today in attempts to understand our world. Gödel’s incompleteness theorems lend themselves to explain that even as we try to compute the world we must acknowledge that within mathematical logic and philosophy this attempt in itself is limited if not paradoxical. Constructing the means to understand our world is dynamic and evolving. To understand understanding, as Von Foerster has said, is to recognise the complexity and interconnectedness of things.[3] It is argued here that intelligence is not an attribute of things but rather a quality of the action between things. We swim in complexity and yet we engage in pursuits of architecture through rhetorical distinctions of discourses and simplicity of agendas that offer little within this deep ecology of interacting agents that stand before us. Our time is radical and yet the discourse and practice of architecture today remains binary, overly simplistic and without deep speculation or risk in attempting to create for this world.

The act to create remains a struggle. To speak of this today without a long-standing commitment to what or how this can be enabled is limited if not counterproductive. Practice in the most expanded sense manifests this commitment. I speak of my own path enabled by this word experimentation that begins with this word space that I would declare is my definition of architecture. If a problem can be considered spatially it is architectural. Architecture is space: time and behaviour its medium. Our conception of the world is understood as something that is in constant strife and flux. The only certainty is uncertainty. Challenged with this conception we embrace a framework that moves away from the habitual and finite means of conceiving design towards one that is dynamic and evolving. The root minima extracted from the complexity sciences expresses a moment of becoming. It is this moment of observation understood at its minima. Form is legible as a moment in time.

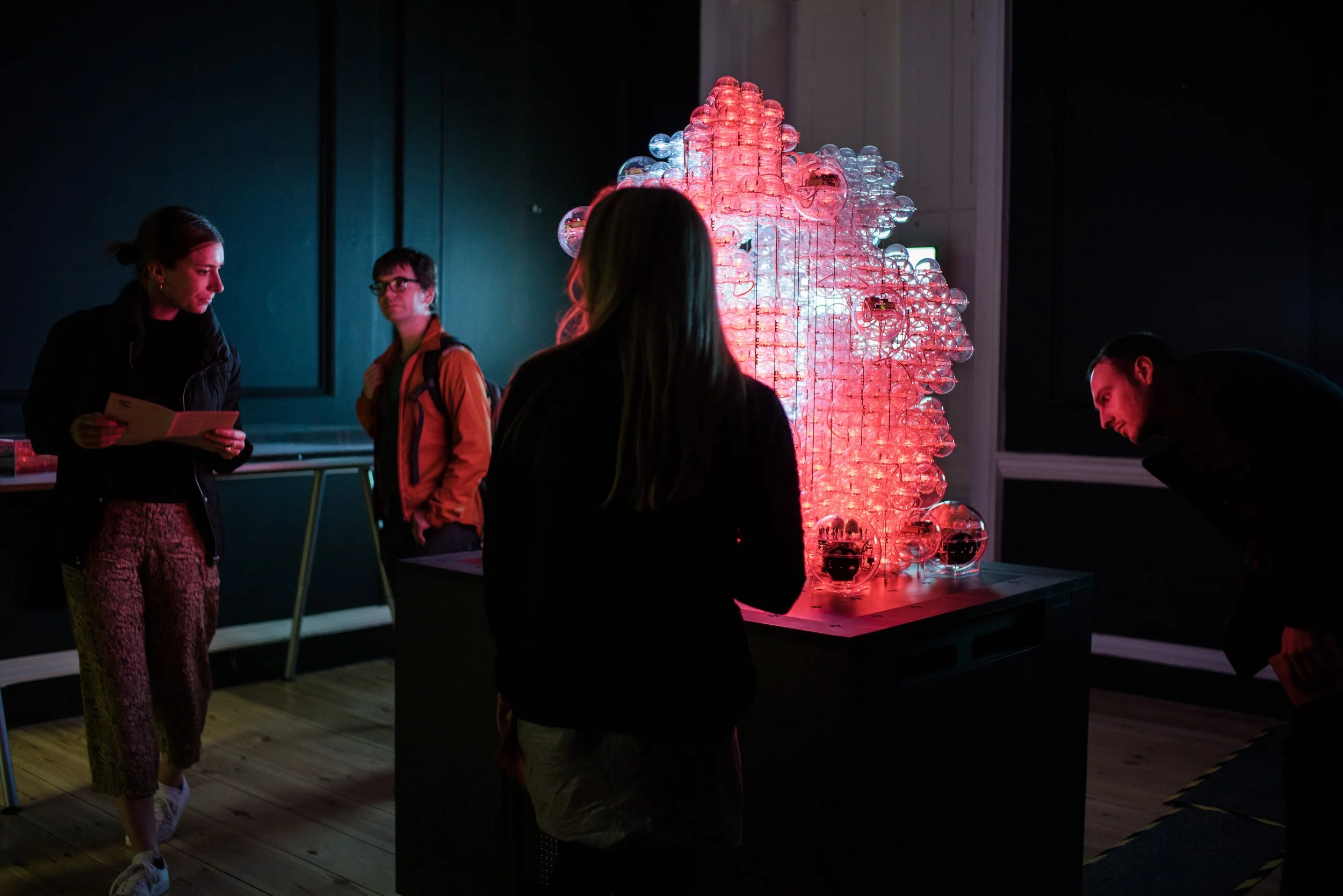

Minimaforms[4] was born from this understanding as an experimental platform to explore space as a cultural interface. Our practice motivated through interventions within the public domain that enable participation and curiosity. Beyond medium or disciplinary distinction our pursuits have set out to explore projects that challenge and articulate a space in-between. The work engages in themes that have ranged from constructed participatory atmospheres that animate the built environment through conversation in works like Memory Cloud[5] to behaviour-based robotics that speculate on emotive relationships with AI robots in projects like the Petting Zoo.[6] Attempts over the last fifteen years have conceptualised frameworks that foster diverse strands of enquiry through design. Unapologetic in our belief that design offers the opportunity to construct environments that are enabling and anticipatory. Things themselves have agency, exhibit life like characteristics and can evolve with us. In our ever-evolving interplay of human-to-human, human-to-machine, and machine-to-machine exchanges, we see agency in our contemporary condition through constructing new means of communication. Within this domain of communication we do not foreground technology, though it is a crucial element of our time. Technology is culture.

Technologies necessitate curious and explorative engagement within the cultural landscape and once out in the world cannot be placed back in the box. Therefore, it is critical that design culture today works on understanding and making accessible, through practice, alternative frameworks for creative synthesis and speculation. In constructing the fundamental relationships of how we live and understand our world we need to examine methods that fundamentally see designing and acting in the world as intellectual enquires. The need for experimentation is not only necessary, it is fundamental to move beyond assertions of what things should be in order to see them for what they can be. Architecture is a conceptual and disruptive pursuit to reexamine and intervene in this world. Anything less would reinforce existing models rather than looking forward and evolving a history of experimentation that embodies the desire to offer more.

In 1984 Andrea Juno and Valhalla Vale interviewed JG Ballard, who was asked his greatest fear about the future. He stated, “I would sum up my fear of about the future in one word: boring. And that’s my one fear: that everything has happened; nothing exciting or new or interesting is ever going to happen again…the future is just going to a be a vast conforming suburb of the soul”.[7] Carlo Rovelli would say that there is no such thing as future in physics.[8] Marshal McLuhan would suggest that what we consider the future is actually our present because we find ourselves living in the past.[9] Considering a future present we may agree “we live in an age where science fiction has become fact. Our contemporary age is as radical with change, latency and uncertainty becoming the new norm”.[10] As we prototype our collective present we may consider that there is no architecture without experimentation. I will not make any more boring architecture. You will not make any more boring architecture. We will not make any more boring architecture…